Final Project: Inferring Space from Sensorimotor Dependencies (ENS Ulm / Univ. Paris Descartes)

Kexin Ren & Younesse Kaddar

Original article: « Is There Something Out There? Inferring Space from Sensorimotor Dependencies » (D. Philipona, J.K. O’Regan, J.-P. Nadal)

The Algorithm

-

One gets rid of proprioceptive inputs by noting that these don’t change when no motor command is issued and the environment changes, contrary to exteroceptive inputs.

-

We estimate the dimension of the space of sensory inputs obtained through variations of the motor commands only with resort to a dimension reduction technique (

utils.PCAorutils.MDS). -

We do the same for sensory inputs obtained through variations of the environment only.

-

We reiterate for variations of both the *motor commands and the environment alike.

-

Finally, we compute the dimension of the rigid space of compensated movements: it is the sum of the formers minus the latter.

Simulation

Notations

| Notation | Meaning |

|---|---|

| Q ≝ (Q_1, \ldots, Q_{3q}) | positions of the joints |

| P ≝ (P_1, \ldots, P_{3p}) | positions of the eyes |

| a^θ_i, a^φ_i, a^ψ_i | Euler angles for the orientation of eye i |

| Rot(a^θ_i, a^φ_i, a^ψ_i) | rotation matrix for eye i |

| C_{i,k} | relative position of photosensor $k$ within eye $i$ |

| d ≝ (d_1, \ldots,d_p) | apertures of diaphragms |

| L ≝ (L_1,\ldots,L_{3r}) | positions of the lights |

| θ ≝ (θ_1, \ldots, θ_r) | luminances of the lights |

| S^e_{i,k} | sensory input from exteroceptive sensor $k$ of eye $i$ |

| S^p_i | sensory input from proprioceptive sensor $i$ |

| M, E | motor command and environmental control vector |

Computing the sensory inputs

where

- $W_1, W_2, V_1, V_2, U_1, U_2$ are matrices with coefficients drawn randomly from a uniform distribution between $−1$ and $1$

- the vectors $μ_1, μ_2, ν_1, ν_2, τ_1, τ_2$ too

- $σ$ is an arbitrary nonlinearity (e.g. the hyperbolic tangent function)

- the $C_{i,k}$ are drawn from a centered normal distribution whose variance (which can be understood as the size of the retina) is so that the sensory changes resulting from a rotation of the eye are of the same order of magnitude as the ones resulting from a translation of the eye

- $θ$ and $d$ are constants drawn at random in the interval $[0.5, 1]$

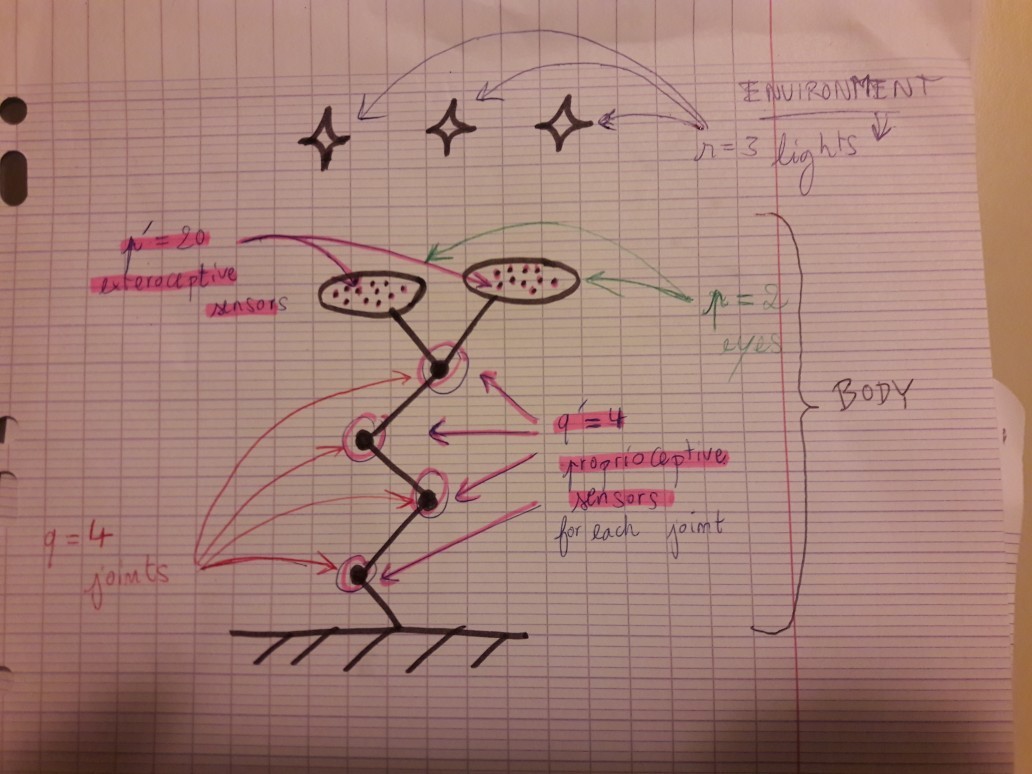

Organism 1

| Parameter | Value |

|---|---|

| Dimension of motor commands | $40$ |

| Dimension of environmental control vector | $40$ |

| Number of eyes | $2$ |

| Number of joints | $4$ |

| Dimension of proprioceptive inputs | $16 \quad (= 4×4)$ |

| Dimension of exteroceptive inputs | $40 \quad (= 2 × 20)$ |

| Diaphragms | None |

| Number of lights | $3$ |

| Light luminance | Fixed |

-

The arm has

-

$4$ joints

- each of which has $4$ proprioceptive sensors (whose outputs depend on the position of the joint)

-

$2$ eyes (for each of them: $3$ spatial and $3$ orientation coordinates)

- on which there are $20$ omnidirectionally sensitive photosensors (exteroceptive)

-

-

the motor command is $40$-dimensional

-

the environment consists of:

- $3$ lights ($3$ spatial coordinates and $3$ luminance values for each of them)

NB: Changes made: typos indices, number of proprioceptive inputs, $S_i^p$ computed with $Q$

Organism 2

This time, to spice things up: we introduce nonspatial body changes thanks to pupil reflex, and nonspatial changes in the environment via varying light intensities.

-

The arm has

- $10$ joints

-

$4$ eyes, each of which as a diaphragm $d_i$ reducing the light input so that the total illumination for the eye remains constant. That is, for eye $i$:

\sum\limits_{ k } S_{i, k}^e = 1i.e.:

d_i ≝ \sum\limits_{ k } \left(\sum\limits_{ j}\frac{θ_j}{\Vert P_i + Rot(a_i^θ, a_i^φ, a_i^ψ) \cdot C_{i,k}-L_j\Vert^2}\right)^{-1} 2. the motor command is $100$-dimensional

-

the environment consists of:

- $5$ lights, of varying intensities

| Parameter | Value |

|---|---|

| Dimension of motor commands | $100$ |

| Dimension of environmental control vector | $40$ |

| Number of eyes | $4$ |

| Number of joints | $10$ |

| Dimension of proprioceptive inputs | $40 \quad (= 10×4)$ |

| Dimension of exteroceptive inputs | $80 \quad (= 4 × 20)$ |

| Diaphragms | Reflex |

| Number of lights | $5$ |

| Light luminance | Variable |

Organism 3

Same as the previous one, except that the diaphragms are controlled by the organism (and not reflex-based anymore).

Note that it should add a dimension to the group of compensated movements: on top what we had earlier, we now have eye closing and opening compensating luminance variations.

For Organism 3, as $d$ is under its control:

where for all $i∈ \lbrace 1, 2 \rbrace$, $W_i$ (resp. $μ_i$) is self.W_i (resp self.μ_i)

Questions

How is the simulation of organism 1 conducted?

The situation is the following: the organism 1 is an “arm with two eyes” comprised of:

- 4 joints (black dots on the drawing), each one equipped with 4 proprioceptive sensors

- 2 eyes, each one equipped, each one equipped with 20 exteroceptive sensors

and an environment constituted of 3 lights.

Recall that proprioceptive sensors are sensors that are NOT sensitive to changes of the environment, they only depend on the body (here: on the position of the joints), whereas exteroceptive may depend on the environment (here: the eyes’ sensors are sensitive to the luminance and position of the environmental lights)

Now, the motor commands are the commands the “brain” of the organism sends to its body (e.g.: “Move the second joint a little bit!”)

Input source include Exteroceptive input (from environment) & Proprioceptive input (from body)?

-

Prioprioceptive inputs are sensory input of the organism that don’t change when the environment does (i.e. they don’t depend on the environment) ⇒ ex: the feeling of your limbs’ location in space, which enables you to know where they are without relying on environmental (e.g. visual) inputs. In our simulation: it’s the feeling of the location of the organism’s joints.

-

On the other hand, exteroceptive inputs and sensory inputs of the organism that may be modified by the environment ⇒ ex: visual inputs: when the luminance/the aspect of the surrounding environment change, your sensory input related to vision changes as well, as you see different things. (same situation in the simulation)

Changes include body change & env. change?

By “body change”, we mean exteroceptive body change, as we get rid of (we ignore) proprioception right away at the beginning, since it doesn’t give us any information on the environment (and recall that what we’re interested in really are the compensable movements, i.e. changes of the exteroceptive body (resulting from motor commands) that can compensate changes of the environment (ex: if the environment is a bag that moves 1meter forward, my body moving forward will compensate the visual input of the bag / if the light I’m looking at becomes twice as bright, half-closing my eyes (diaphragm) will compensate the visual input too (since the doubled luminance will be halved))

Sensors are all on body, but include exteroceptive sensors (for body+env. changes) +proporioceptive sensors (for body changes only)?

Yes indeed! Sensors are on the body the organism we’re considering. Basically, the approach is this one: we put ourselves in the organism brain’s shoes: all we can do is:

- issue motor commands (ex: brain tells the arm to move / tells the eyes to close themselves, etc…)

- observe environmental changes

and then we collect sensory inputs, which are twofold: the proprioceptive ones (ex: the position of your tongue in your mouth), and the exteroceptive ones (ex: the visual input (what you see)). Then, to learn more about the physical space in which the organism is embedded, we focus on the exteroceptive inputs, since they are the ones that react the environmental changes. And in particular, we pay close attention to the much-vaunted compensable movements, i.e. the situations like these:

- Step 0: a fixed exteroceptive sensor has a value x (ex: looking at an object in front of us, the sensors being the cone cells in the retina)

- Step 1: a environmental change dE modify this value (it can be modified by environmental change as it is exteroceptive) and set it to y (ex: the object moves 1 meter forward: it looks smaller, as it is farther)

-

Step 2: we notice that there exists a certain motor command dM that can bring this exteroceptive value back to x: the brain orders the legs to walk one meter forward, and then we see the object looks exactly as big as before.

So $dM$ compensate $dE$ ⟹ in the $Motor × Environment$ manifold: adding $dE$ and then $dM$ to our starting point $(M_0, E_0)$ (thus getting $(M_0+dM, E_0+dE)$) brings us back to the same sensory input! In other words: φ((M_0, E_0)) = φ((M_0+dM, E_0+dE))

And these special compensable movements are exactly what stems from the notion of the physical space in the sensory inputs: in the previous example, it’s the notion of relative distance between the organism and the object in the surrounding world (hence a spatial property) that is the same in step 1 and step 2, and that makes the sensory input be same.

What’s the influence of the 3 conditions of Diaphragms: (1) None / (2) Reflex / (3) Controlled

Here the diaphragm is basically the eyelid of the organism: it can either never change, of change not on purpose (reflex), or change by the willingness of the organism. That’s pretty important, because if the organism can control its eyelids, it can compensate itself the changes of the environment luminance (e.g. by closing a little the eyes if the luminance is increased, etc…).

But in simulation 1, the organism is not able to issue such motor commands as “close the eyes”, since it doesn’t control the diaphragm. The diaphragm condition is important because it empowers the organism with the ability to compensate luminance, which wasn’t possible before: so the group of compensated movements is of higher dimension, since it encompasses now all the changes of the form $dM$=”close/open the eyes a little bit”, $dE$=”the luminance changes” in addition the previous space-related ones.

What do we mean by proprioceptive body?

It’s sort of a misuse of language (to be more concise), but what is actually meant by “proprioceptive body” as far as I know is “the body, accessed through all its prioprioceptive sensory inputs and only them”.

Ex: let’s consider the pokémon Haunter for example:

Here, proprioception encompasses locating his hands and body in space, and exteroception consists in visual inputs from its eyes and gustatory perception in his mouth. So the proprioceptive body in this case would be the information about the body the brain gets from proprioception only, i.e.: only its limbs location in space (not the visual/gustatory cues its gets from the environment via its eyes and mouth).

In other words: the proprioceptive (resp. exteroceptive) body is “all the body parts dedicated to proprioception (resp. exteroception)”, so to say.

Ex: in our case (organism 1):

- the joints are equipped with proprioceptive sensors

- the eyes with exteroceptive (“retina-like”) sensors

So describing the exteroceptive body is specifying a set of parameters sufficient to describe the states of the exteroceptive sensors. When the sensors are in two different states, they won’t have the same value for the same environment (ex: an eye in two different positions won’t see the same thing, even if the environment doesn’t change: so the position of the eyes is part of their state). Here, the states of the exteroceptive sensors (= sensors on the eyes) can be described by the position of the eyes (3 parameters for each eye), and their Euler angles (3 parameters for each eye).

What’s wrong with our results?

The whole point is to have the organism discover itself the environment and its exteroceptive body. Obviously, we as programmers know how they are generated (cf. the compute_sensory_inputs method): but the organism doesn’t know: and what it does is making its motor commands and the environment positions vary randomly, and then compute the number of parameters needed to describe the exteroceptive inputs variation when

- only the body (motor commands) moves

- only the environment changes

- both the environment and the body change

The results we’re supposed to get are around:

| Characteristics | Number of parameters necessary to describe |

|---|---|

| Exteroceptive body | 12 |

| Environment | 9 |

| Body and Environment simultaneous changes | 15 |

| Group of compensated movements | 6 |

(approximately, because all of this relies on random data, I don’t think we can hit the spot each time)

But we’re not there! We’ve tried a whole bunch of things, higgledy-piggledy: change the neighborhood size (bigger, smaller, …), the generating number of motor commands, environment positions, the number of pairs of variation (environment × motor), the random seeds, etc…

For example, with 500 generated motor commands/env positions (vs. 50 in the paper), we get:

| Characteristics | Number of parameters necessary to describe |

|---|---|

| Exteroceptive body | 3 |

| Environment | 5 |

| Body and Environment simultaneous changes | 11 |

| Group of compensated movements | -3 |

⇒ the number of parameters for body+environment is pretty close to what it should be (15), so that’s fine at this point. But there is a huge difference between the number of parameters we’re supposed to have for the body only (12 instead of 3), and the environment (9 vs. 5, even if it’s better for the environment).

A very important parameter we had completely overlooked at first is the variance of the $C_{ik}$, which can be thought of as the size of the retina! In the article, no explicit value is provided for this variance, but this is the most important remark in the article:

The $C_{i,k}$ are drawn from a centered normal distribution whose variance, which can be understood as the size of the retina, was so that the sensory changes resulting from a rotation of the eye were of the same order of magnitude as the ones resulting from a translation of the eye.

Unfortunately we can’t find any “reasonable” retina size value for seed=1 and seed=2 (random seeds): what we mean by “reasonable” would be a retina size such that, by denoting by:

compthe dimension of the rigid group of compensated movementsbody(resp.env, resp.both) the number of paramters necessary to describe the body (resp. the environment, resp. both of them)

then:

both > bodyandboth > env(changing both the body and the environment should yield a higher dimension than just the body and just the environment!)body + env ≥ both(by the Grassmann formula)body = 12(because all we need is 12 parameters to describe the body: 6 (3D position & Euler angles) for each eye)- and

comp = 6: the dimension of the Lie group of orthogonal transformations (3 translation and 3 rotations).

Implementation

OOP

Object-Oriented Programming is a programming paradigm (“way of of coding”) relying on the notion of objects and classes (which are blueprints for object, so to say). A class (ex: a class Person) has

- attributes which are characteristics of the object. Ex:

nameandagecan be an attributes of ourPerson:class Person: __init__(self, age, name): self.age = age self.name = nameNB: the keyword

selfrefers to the object itself. -

and methods, which are actions they can take. In practice, these are functions inside the class. Ex:

walk()orsay(something)can be methods of ourPerson:class Person: __init__(self, age, name): self.age = age self.name = name def walk(self): # [...] def say(self, something): print(something + " !")NB:

__init__is a special method that is executed when an object is created- all the methods have

selfas first argument

Now, an object, is a particular instantiation of our class: in our example, it’s would be a particular Person:

# We create a `Person` aged 68 and called `"Grassmann"`

Grassmann = Person(68, "Grassmann")

# We make this person say something

Grassmann.say("dim(E+F) = dim(E) + dim(F) - dim(E ∩ F)")

And what is convenient is that a class can inherit from another one (i.e. inherit from the attributes and methods of another one). Ex: a class Mathematician can inherit from the class Person (as a mathematician is particular instance of a person), and it would have its own new methods, such as create_theorem() that Person doesn’t have.

In our case:

- each organism will be a class

- and organisms 2 & 3 will inherit from organism 1